Out of the Box: Object Lessons

For over 80 years, the Kentucky Museum has been a place for Kentuckians to know Kentucky. We’ve collected over 25,000 artifacts including fine art, textiles, decorative arts, archaeological specimens, and toys.

These artifacts are stored, classified, and even displayed in boxes. But what happens when you take an artifact out of its box?

Uncover how artifacts in our collections fit in multiple boxes—and multiple fields of study—while showcasing the unique ways our community developed. Observe things you know, and discover things you don’t, by going “out of the box.”

Caves

There is a hidden, spectacular “bonus” landscape winding through more than 600 miles of caves beneath the familiar, surface world of southcentral Kentucky. Over 400 of these make up the Mammoth Cave System, Earth’s most extensive known cave. Starting more than 4,000 years ago, ancient Native Americans, entrepreneurs, adventurers, slaves, and curiosity seekers have wandered its depths.

What are their stories?

by Dr. Chris Groves

Mineral formations such as stalactites and stalagmites that grow from cave ceilings and walls, collectively called speleothems, add great beauty to many cave passages. Although sandstone layers overlying the cave prevent downward migration of water inhibiting the growth of speleothems in some of parts Mammoth Cave, there are indeed areas of the cave and others nearby in which they grow profusely.

Other than the aesthetics of speleothems, analysis of chemical constituents within them called isotopes can provide a rich source of information about past conditions the region around the cave over thousands of years, including past temperatures, rainfall patterns, and what kinds of plants grew in the area. Our ability to plan for future climate change is deeply informed by records of past climates, and speleothems provide one of Earth’s richest sources of that information.

Object No. 944, 973, 949 and 1987.35.7

by Dr. Guy Jordan

After his wife died in 1857, painter and photographer Clement Reeves Edwards moved to Bowling Green from Cincinnati, Ohio. While his portraits, of which the Kentucky Museum owns ten, and his photographs provided his main source of income, Edwards also produced a number of landscape scenes, including one of Jennings Creek (also in the Kentucky Museum’s collection). This painting—dark, inky, and mysterious—may depict a wedding party gathered in what was called the “Bridal Chamber” along Mammoth Cave’s “Gothic Avenue.” Nine weddings were known to have taken place in the chamber between 1851 and 1892. The solemnity and grandeur of the setting would have proven a dramatic although unconventional backdrop for the exchange of vows.

Object No. 1979.2.2

by Dr. Kate Hudepohl

Hyman Gratz developed Mammoth Cave as a tourist attraction in 1816. He created the first Mammoth Cave Hotel near the Historic Entrance from cabins that had been used to house slaves who mined saltpeter for use in gunpowder. The saltpeter operations declined after the War of 1812, when the demand for potassium nitrate waned. The former manager of the saltpeter mining operation, Archibald Miller, served as the first cave guide.

The hotel was modified several times by subsequent owners. In 1838, Franklin Gorin connected the cabins to create a continuous building. After Louisville physician John Croghan purchased the Mammoth Cave Estate in 1839, he added a dining room and ballroom.

The first Mammoth Cave Hotel burned in 1916. A new hotel was built in 1919 and remained in place until a third iteration of the hotel was constructed in 1965. The existing hotel has undergone several renovations and recently reopened to visitors.

Object No. 1971.3.51

Originals may be viewed at the WKU Department of Library Special Collections.

- "The Subterranean Voyage, or The Mammoth Cave, Partially Explored" by a gentleman in Bowling Green, January 21st, 1810.

- Helm-Lucas papers on a double wedding in Mammoth Cave of Anna Moore to T. N. Moody and Jennie Lucas to J. W. Helm, November 12, 1879.

- "Between a Rock and a Radio Place: The Case of the Irene Ryan Signature Mystery" by Peggy Gripshover and Chris Groves.

- Mammoth Cave also featured prominently in issues of WKU's The Elevator. Volume 1, No. 8 (July 1910) features "Echoes from Mammoth Cave" (page 9-15 of the PDF) while Volume 1, No. 9 (July 1911) features "Report from the Walking Trip to Mammoth Cave, June 8-13, 1911" (starting on page 14 of the PDF).

Carrie Burnham Taylor

History suggests that as “big business” started to take hold in the late 1800s, women became more involved in business and working outside the home. However, few women owned companies. Those that did were in industries centered on women, such as home goods, apparel, or personal care.

Today, women own only 40% of businesses in the U.S., making Carrie Taylor’s business of the early 20th century that much more impressive.

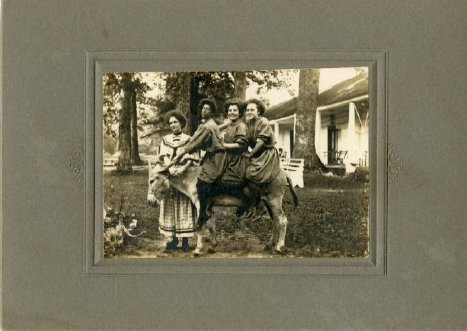

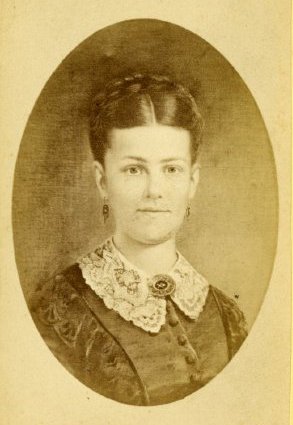

Carrie Taylor was a dressmaker who began her business, the Mrs. A. H. Taylor Company, in 1878. She designed fashions for individual women and employed many women who hand and machine-sewed her designs. She shopped for fabric and trims in Europe and designed unique garments for individual clients. Her success was due to the reputation she gained from her attention to detail, her creation of elaborately designed garments, and excellent workmanship.

by Dr. Kate Hudepohl

Carrie Burnam Taylor established and oversaw a thriving dressmaking business in Bowling Green from the late 19th century through the early 20th century. Taylor developed the business early in her adult life and continued running it until her death in 1917. For nearly 40 years, the Mrs. A.H. Taylor Company was known for quality, lace-embellished dresses.

Part of her success stemmed from a clientele base developed among the students of the Potter College for Young Ladies. Students, drawn from various parts of the South and Southwest, purchased custom-made dresses for various occasions. Continued patronage when students returned home provided word-of-mouth advertising for Mrs. Taylor’s dresses.

Object No. 1990.131.12

by Dr. Carrie Cox

We don’t walk around with rectangular pieces of fabric awkwardly belted, pinned and waded up to fit our bodies. No, we rely on fashion designers to create fashions that fit our bodies, but how? It begins with controlling fullness. Designers turn 2-D fabrics into 3-D garments using a variety of techniques to control fullness. They gather (or shir), pleat, dart, and tuck fabrics in elaborate ways. They also apply elastic, drawstrings in casings, yokes and use seaming and knit fabrics that expand and contract to fit our bodies.

What techniques did Carrie Taylor use to control fullness in 1906? As we explore the shirtwaist, we can identify that she used shirring on the front and back shoulder areas. There are pleats on the front of the bodice. She shirred the sleeve cap to create a full sleeve at the top. The skirt is a series of gores that narrow at the waist, thus controlling fullness with seaming.

Object No. 1955.17.1

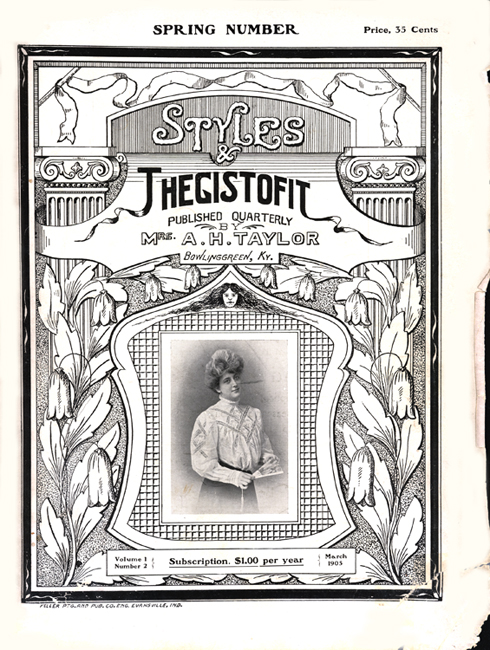

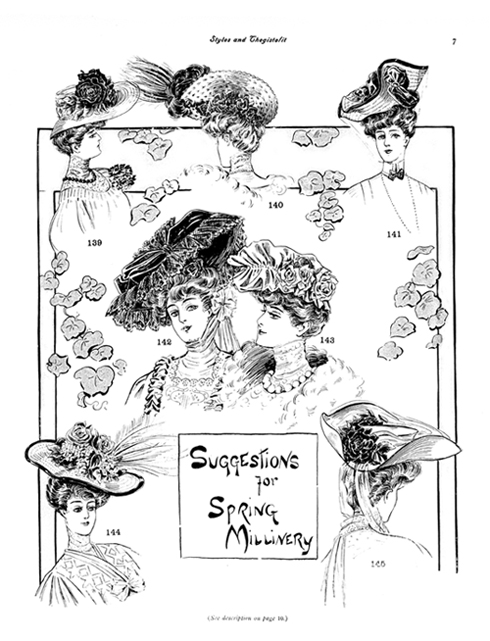

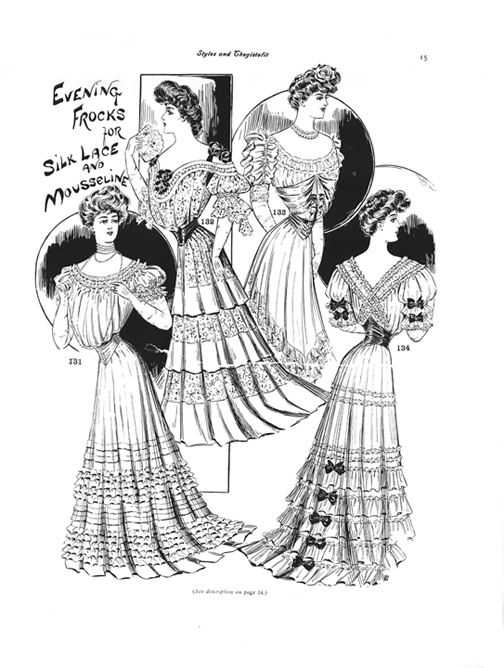

Styles and the Gist of It

by Dr. Carrie Cox

Fashion plates are drawn illustrations of clothing that highlight new or current fashionable styles. Though a single illustration, they functioned as magazines in the 19th century before photography or periodicals existed for fashionable women to see the latest styles. During this century women used fashion plates to show their dressmakers the style they preferred. All clothing was custom-made, meaning your clothing was made to fit your body and with the fabric and details you desired. Dress makers were skilled at using the fashion plates as a guide to create fashionable clothing for women who were not skilled at sewing.

Carrie Taylor, modest of Bowling Green, KY created sample cards with illustrations of her designs and paired them with fabric and trim samples. Sample cards, similar to fashion plates, helped clients know their options and make choices based on what Taylor would create.

While Ladies Home Journal, the Delineator, and Vogue were in publication in 1906, Carrie Taylor was selected to design and construct this elaborately detailed, blue shirtwaist and matching skirt. Her design matches the fashion of the time, but it is uniquely made to fit the wearer and uniquely designed by Taylor.

Additional Resources, including Mrs. Taylor's company records, may be viewed at the WKU Department of Library Special Collections.

Click here to view digitized records relating to Mrs. A. H. Taylor online in KenCat.

Music: Home and Sacred

Before the availability of the radio and phonograph, music in the home was a do-it-yourself affair. Many people played musical instruments, such as the piano and violin. Mountain music, the folk music of Appalachia, came with the English, Irish and Scottish immigrants who settled there. Traditional musicians learned ballads and dances by ear, a tradition that continues to this day.

Sacred music also played a role in the home and in church. Parlor songs could employ religious imagery, while church music took various forms. More homespun music appears in the singing schools of Kentucky and Tennessee, as itinerant singing masters went from town to town, giving classes in reading shape notes and singing hymns.

by Tiffany Isselhardt

In 1877, Thomas Edison sought to make a machine that could transcribe messages that could be used repeatedly. Within the year, his experiments led to the phonograph and the first recorded message: the nursery rhyme “Mary had a little lamb.”

Edison’s machine was an instant success, and he envisioned many uses, including what we know as dictation, music recordings, oral histories, language preservation, and telephone messages. By 1891, Edison was using cylinders like these to create talking dolls and coin-slot phonographs. In 1896, he manufactured Edison Home Phonographs—and their accompanying cylinders—for home use. Though limited to 4 minutes per cylinder, people all over the world could now listen to music whenever they wished.

Edison’s invention pioneered the technology we now use in radios, voicemail, voice recorders, music discs, and jukeboxes.

Object No. 3008 / 4567 and 1958.80.1

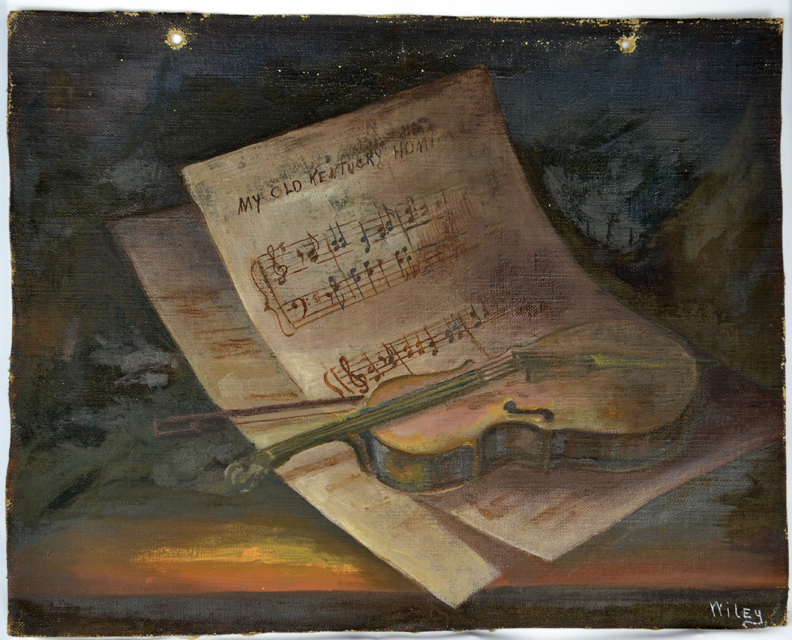

by Dr. Guy Jordan

Grace Kirby Wiley (1877-1952) is a Kentucky artist known for her exuberant still-lives of flowers. While she trained at the Cincinnati School of Art, she spent most of her life in Smith’s Grove. Her painting “My Old Kentucky Home” features a fiddle set down upon sheet music of the iconic 1853 Stephen Foster ballad which, in 1928, became Kentucky’s official state song. The fiddle and music hover above a distant sunset which evokes the song’s appeal to nostalgia for days gone by.

Foster seems to have written the song from the point of view of a slave—probably based on the title character from Louisa May Alcott’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)—who had been sold out of Kentucky to a large deep-south plantation where his labor was harder and his life more difficult. The song was later reinterpreted as a paean to the bygone days of antebellum white power and economic prosperity, built upon a racist foundation of slave labor.

In 1986, the Kentucky State Legislature changed three appearances of the word “darkies” in the lyrics to “people.” Today, “My Old Kentucky Home” is considered by many as a more general expression of homesick admiration for Kentucky without the racial overtones of the original lyrics. Yet the origins, context, and meaning of the song remain controversial.

Object No. 2005.37.3

"Singing Schools"

In 1987, WKU Folklife student Teresa Hollingsworth conducted an oral history interview with Zilpha Amanda Hume concerning her husband's (Archie Hume's) singing schools where he acted as a singing school instructor. Click below to listen to this 1-hour interview on SoundCloud, or listen in our mobile app.

Click here for a PDF transcription.

Song chart for a singing school.

Additional Resources, including sheet music and documents on the Shakers at South Union, may be viewed at the WKU Department of Library Special Collections.

Medicine

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, access to medical care was limited, particularly in rural communities. In some larger towns in Kentucky, hospitals and doctor offices were available. Locally, citizens could receive care at places such as the Blackburn Hospital, Graves Gilbert Clinic, and Dr. Otho D. Porter’s office. In more rural areas, care was provided by doctors such as Dr. Neel of Drake, Kentucky, and nurses who traveled to patients’ homes on horseback.

Infectious diseases such as tuberculosis were also more common and lethal. Today prescription drug therapy is common; however, in the early to mid-1900’s this was not the case. Physicians provided the limited medicines available at the time of care. In most cases, treatment during this time was supportive and not curative. Some of the medications that were common then are still used today. Similarly, many individuals were drawn to the use of alternative health remedies. Most of these remedies were not well studied, and some were later found to contain dangerous ingredients.

by Tiffany Isselhardt

Dr. Gottlieb's Fisch Bitters and The Fish Bitters were sold in bottles like these. Desgined in 1866, William Harrison Ware used the bitters recipe of "Dr. Gottlieb Fisch of Berlin, Prussia" and this unique bottles to sell bitters from 1866 to 1882. The bitters were meant to cure "dyspepsia, general debility, languor, loss of appetite and any complaint requiring a tonic bitters" including alcoholism. Later, fish-shaped bottles based on this design were used by Eli Lilly & Company to sell cod liver oil. Given the bottle's off-center design, it was likely made in the 1860s by Ware & Schmitz at 3-5 Granite Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Object No. 1966.1.6

by Dr. Kate Hudepohl

Louisville physician John Croghan, a tuberculosis specialist, purchased the Mammoth Cave Estate in 1839 to develop it into a treatment site for patients. Because symptoms of the disease included coughing and chest congestion, it was thought that air quality may affect the disease. Based on reports of visitors feeling positive physical effects after spending time in the cave, Dr. Croghan decided to build a tuberculosis sanitarium inside the cave.

Two stone structures and several wood structures were constructed by slaves to house 15 patients during 1842-1843. Unfortunately, living in the damp cave and breathing smoke from cooking fires hastened the disease’s progression. Five patients died before the sanitarium was closed.

Remnants of the stone tuberculosis structures remain in the cave today. Three of the patients are buried in the Old Guides Cemetery at Mammoth Cave National Park.

Object No. 1996.170.31

Additional Resources are linked in the PDFs below. Originals may be viewed at the WKU Department of Library Special Collections.

- "Oliver Hazard Perry to Orlando Brown, 21 December 1842" written during his time at Penseco Cottage in Mammoth Cave.

Religion

Whether celebrated in church, at home, or in outdoor gatherings, religion plays an integral role in Kentucky life. Anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1926-2006) stated that religion “is a system of symbols which act to establish powerful, persuasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in humans.” As symbols, what do the objects, photographs, and records on display here tell us about how religion is practiced in South Central Kentucky?

by Dr. Kate Hudepohl

The Shakers, also known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, were founded in the mid-eighteenth century in England and moved to the United States in 1774. Settlements started in New York and spread from through parts of New England. Missionary efforts initiated settlements in the Midwest, including two in Kentucky: Pleasant Hill and South Union.

Shakers valued gender and class equality and promoted four virtues: virginity (celibacy), confession, communal living, and separation from the world. Because celibacy was a key virtue, new members were acquired through conversion and adoption. The term “shaker” originated from trembling adherents experienced during rituals which was interpreted as a sign of sin leaving the body through God’s grace.

The settlement at South Union functioned from 1807 until 1922. At its height, it comprised 225 buildings and 6,000 acres of land. Today the Shaker Museum at South Union owns and manages part of the remaining settlement for tourism and educational purposes. The only active community is Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in Maine.

Object No. 2011.3.32

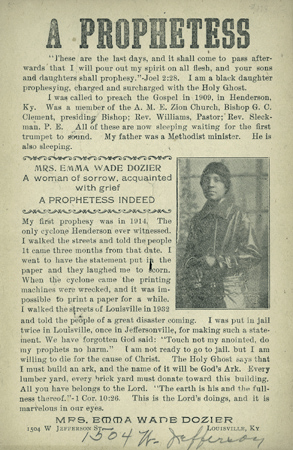

by Dr. Isabel Mukonyora

This broadside outlines the life and clairvoyant experiences of Emma Wade Dozier, an African-American (Black) "Prophetess" minister-preacher in Louisville, Kentucky. Dozier claimed to have predicted the 1914 cyclone in Henderson, Kentucky. "I am a Black daughter prophesying, charged and surcharged with the Holy Ghost."

“A woman of sorrow acquainted with grief,” is a moving way of reminding us of the pain caused by slavery. Miss Emma Wade Dozier hit the headlines as a Christian slave so acquainted with oppression she made public her theology of the cross.

Object No. 1992.133.1

by Dr. Isabel Mukonyora

Black and white photograph showing the interior of the St. Joseph Catholic Church in Bowling Green, which tells the story of Irish people who in addition to building the railway close by, built for themselves a house of worship between 1867 and 1880. They used many objects in their worship, including this humeral (or benediction) veil. Anyone who visits Ireland in Spring will know that yellow daffodils announce spring and Easter too. This beautiful cloth could have been used to cover the chalice at Eucharist at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church.

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1926-2006) concluded that religion is “a system of symbols which act to establish powerful, persuasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in humans.” Our Irish friends did not stop there. They left behind a busy railway line and fine Catholic school.

Object No. 1999.121.1 and 1971.54

by Dr. Isabel Mukonyora

This beautiful pink silk cloth is more than a handkerchief. To this day, cloths like this are used to celebrate the Eucharist by Catholics, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and/or Methodists. If interested in finding out more about women’s creative work with cotton and silk, ask for the collection of data on the Shakers!

Object No. 1985.6.1

by Dr. Guy Jordan

Mordecai Ham was born in Allen County, Kentucky in 1877 and graduated from Ogden College. He was one of the most prominent traveling preachers of the early 20th century.

Like the “camp meeting” religious awakenings in early 19th Century Kentucky, Ham’s revivals converted thousands of people to Christianity. In 1934, during a revival in Charlotte, North Carolina, Ham’s sermon convinced a teenager named Billy Graham to make a commitment to Christ. Ham was also a prominent supporter of the temperance movement and the 18th Amendment to the Constitution which prohibited the “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.”

This photo depicts one of Ham’s early revivals on the corner of Main and Center streets in downtown Bowling Green.

Object No. 1977.51.182

by Dr. Guy Jordan

The Colored Methodist Church was founded by 41 former slaves in Jackson, Tennessee, in 1870. It retained its original name until 1950, when it was renamed the Christian Methodist Church. While the particular church depicted by Wilson on Russellville Road no longer stands, the CMC remains vibrant with 800,000 members in the United States and across 14 African Nations. The artist of this piece, Ivan Wilson, was a longtime professor and department head for the art department at WKU. In 1973, the Ivan Wilson Fine Arts Building was named in his honor.

Object No. 1986.69.2

Additional Resources, including records of local religious organizations, may be viewed at the WKU Department of Library Special Collections.

Credits

Thank you to the Department of Library Special Collections for loans of historical images and documents presented on this site. Special thanks to our faculty contributors and partners who curated content for the exhibition:

- Spencer Cole, Instructor, School of Nursing

- Dr. Carrie Cox, Assistant Professor, Applied Human Sciences

- Dr. Kate Hudepohl, Associate Professor, Folk Studies & Anthropology

- Dr. Christopher G. Groves, University Distinguished Professor of Hydrogeology

- Dr. Guy D. Jordan, Associate Professor, Art

- Dr. Eve Main, Professor, School of Nursing

- Dr. Isabel Mukonyora, Professor, Philosophy & Religion

- Dr. Whitney O. Peak, Associate Professor, Management

- Dr. Mary E. Wolinski, Professor, Music

- Dr. Dawn G. Wright, Professor, School of Nursing

Sponsored by Dr. Michael and Susan Collins, Kentucky Humanities Council, and the Kentucky Local History Trust Fund (KRS 171.325), a program administered by the Kentucky Historical Society.

Some of the links on this page may require additional software to view.